Liberating states: Utopia and Temporary Autonomous Zones

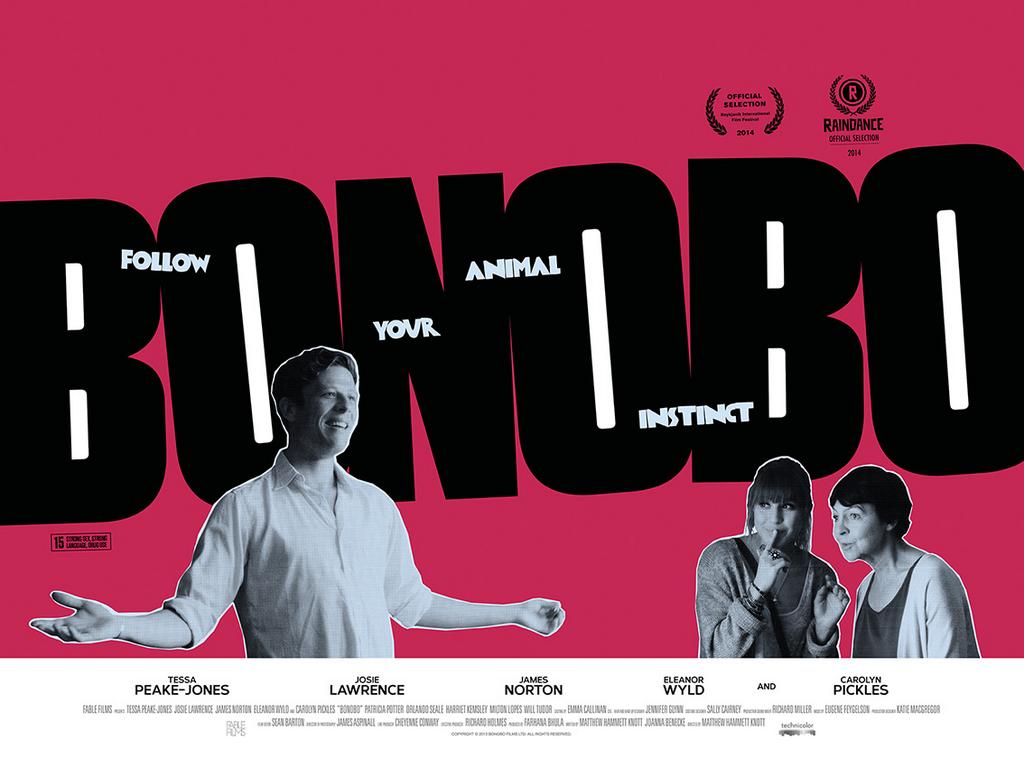

In the new film Bonobo, Judith (Tessa Peake-Jones), a straitlaced, middle-aged widow tries to reconnect with her estranged daughter Lily (Eleanor Wyld), who has fled to a libertarian commune in the English countryside. The commune’s policies are modeled after the polyamorous primate of the film’s title: all members of Bonobo must resolve conflict through sex or intimacy;lunch is hand-fed by other Bonobos (self-serve is strictly prohibited) and clothing is optional. Lording over the premises is 55 year-old Anita (Eastenders’ Josie Lawrence), a sunny bohemian in flowing hair, exotic gowns and tribal jewelry – the den mother to a collective of libidinous twenty-somethings. There’s brazen, naked-yoga expert Ralph (James Norton), the group’s resident trickster and provocateur; the sparring pregnant couple Malcolm (Orlando Seale) and Eva (Patricia Potter), and footloose and fancy-free interracial lovers Peter (Milton Lopes) and Toby (Game of Thrones’ Will Tudor).

It is the process of watching Judith unravel and question her own inhibitions, and the hijinks that ensue when she interacts with the various Bonobos and maneuvers the various dynamics, that form the crux of the story. Director Matthew Hamett Knott answered a few questions about the making of his first film, utopia, counterculture and the fine balance between comedy and drama.

Did you imagine Bonobo as a utopian setting when you first came up with the concept for the film?

I wanted to write about people who set out to create a utopia but who were foiled by both their own assumptions and the reality of human nature. I always conceived Judith as the protagonist, so I envisaged the commune from her perspective, as somewhere exclusionary and not necessarily welcoming to outsiders. To me, that is no utopia.

How sustainable would you say the lifestyle is?

I’m not making any wider judgment on communes or alternative lifestyles, but within the narrative of Bonobo, the whole point is that they’ve created an unsustainable lifestyle. They’ve failed to take into account various perspectives beyond that of the young, desirable and highly sexually charged. Older women, pregnant women, gay women… all have different needs and desires which call the simplistic bonobo philosophy into question. And yet, I hope the film retains the idea that as a liberated and liberating way of thinking, it has something to offer.

The film points a finger at certain middle class values and received behaviour, but it sneers at liberationists & ideologues as well. Where is the happy spectrum?

If I sneer at anything its at presumptive values rather than the people who hold those values. I feel the character I am least generous to is Celia, the neighbour, but she could be Judith in another version of the tale (as is hinted by the film’s ending). Really, she’s more trapped than anyone. If there is a happy medium, it is being open-minded and inclusive, regardless of your own personal ideals. I tried to show that liberals are as bad as conservatives at excluding certain demographics from the sexual conversation.

Several archetypal traits seemed to be adopted by the Bonobos. You had the lovers – Malcolm & Eva, Ralph the trickster, Toby the angel, Peter the other, Lily the daughter, Anita the whore (arguably), and finally Judith, the mother. Could you describe the process that went into creating the different dynamics between the groups?

If there is a whore in that commune it is Ralph, although I’d only ever use that word as an archetype that needs dissembling. I’m sure Anita has been regarded as a sexual reprobate in the past by the likes of Celia, but really, I see her as a mother in search of a family. I do like to play with archetypes but only in order to reveal that the characters are so much more than that. So we meet Judith as a mother, and only a mother, but soon discover that by defining herself in such a role she has been severely, some would say tragically, limiting her horizons.

At one point in the film, Lily seems to experience anxiety over her privilege being exposed to her fellow Bonobos. What was the back story on that?

It’s interesting you picked up on that. I think Lily’s is a classic case of rebellion. She has felt stifled by her mother’s conservative values and has sought to embrace the opposite. In doing so, clearly she has presented something of an artificial front to her new comrades. The funny thing for me is that they are mostly all just as privileged as she is and aren’t at all bothered to learn the truth.

Mention was made of the characters sustaining themselves off labor. What kind of thought went into placing the characters into a socioeconomic context?

It was actually a question that people asked following initial test screenings — how do these people sustain their lifestyle? We added in some information to that effect in reshoots that were scheduled for other reasons. But although there is some pretence at sustainability, I see these characters as people who have been privileged to remove themselves from the demands that are placed on most people’s lives.

What qualities did the actors need to possess in order to be prepared for the content of the film?

There were some actors who ruled themselves out on the basis of the sex scenes and nudity. But really, the hardest thing was finding actors whose performance style fitted the tone of the film. It’s a fine balance between comedy and drama, and I wanted actors who were able to push it comedically, but still make their roles authentic. Luckily, we found a few.

Can you share a story about a challenge that came up due to the nature of the material?

I really wanted to include a scene where two men had penetrative sex. Not for the shock value, but because it’s something I imagined a lot of my audience had never seen depicted on screen, and I think people genuinely have misconceptions about what it actually looks like. So we had to get technical about it and I drew diagrams and had a few very specific conversations with the actors. It’s the kind of thing nobody ever talks about. But it’s that level of planning that allowed them to perform something which, I hope, ends up looking very natural and normalized.

Some of the characters experience stress and conflict because of their interpretations of the lifestyle – Malcolm, Eva, Anita; and later Ralph. During talks with any of the actors, did you ever equate sexual openness with chaos?

I think one of the reasons the bonobo philosophy falls apart is because it is founded on certain assumptions that leave open the potential for chaos, or at least a lack of boundaries. For example, the idea of using sex to resolve conflict fails to take into account the fact that sex can be aggressive and even used as a weapon. That is what Ralph ends up doing and it has serious consequences for the commune.

What would you say is a defining feature of England’s counterculture heritage?

It feels constantly under threat, and not always from the usual suspects. I think the nature of public arts funding can create a culture of censorship and self-censorship at times. But I would say the defining feature of Britain’s counterculture is that it exists in some form, has existed for a long time and feels inevitable. That’s a liberating state of affairs for artists. – Jordan Mattos @jordantees

Follow @bonobosfilm & Watch the UK trailer now !