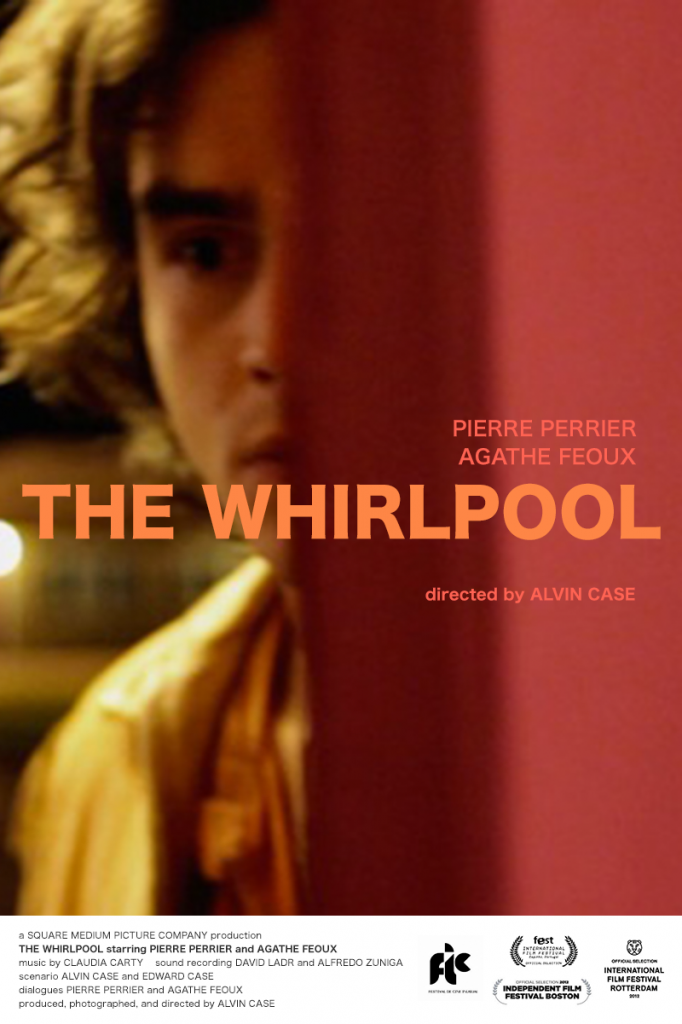

Doomed Romance Cinema: Director Alvin Case on THE WHIRLPOOL

The Whirlpool premiered at International Film Festival Rotterdam in the Bright Future category, which “presents adventurous new work by novice makers”. Basically, premiering under the Bright Future section is an excellent way to make a splash. Chances are your work is uncompromising, difficult to embrace in one sitting, and leaves you with more questions than answers.

The Whirlpool premiered at International Film Festival Rotterdam in the Bright Future category, which “presents adventurous new work by novice makers”. Basically, premiering under the Bright Future section is an excellent way to make a splash. Chances are your work is uncompromising, difficult to embrace in one sitting, and leaves you with more questions than answers.

Described by writer director Alvin Case as “a transatlantic collaboration over emails and video chat between french actors Agathe Feoux, Pierre Perrier (of Sundance TV’s The Returned)” and himself that “lead to a riff on memorable doomed romance cinema “, the film’s scenes were improvised and filmed on location in Paris, France and Niagara Falls, Ontario and New York.

At Indiepix we like our films to be socially conscious and unabashedly political. How would you say the film fits into that context?

The Whirlpool is more of a pure art film dealing with the dynamics of men and women, sexual and emotional interactions, and the wanderlust that comes with being born into a first -world country.

There’s an affinity for the tradition of the art film, for sure.

Art films have always been the foundation for the aesthetics of cinema because experimentation and breaking rules are part of the methodology. It’s where techniques are discovered and refined before they show up in more traditional films. Art films are for the most part, polemic free so they often increase in stature over time, no matter how strange or incomprehensible. Think of Bela Tarr or Davide Manuli as contemporary examples.

The film premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival. Can you describe your experience of screening the film there, and the reception of the audience?

The people who go to see films at Rotterdam are people who seek out new cinema, new ways of telling film stories. This is the atmosphere that dominates Rotterdam. It’s a vibe of possibility and embracing of experimentation. It’s awesome for a filmmaker to be in this atmosphere. The best festival audience I have experienced thus far. And they come up to you in the streets to tell you how they felt about viewing your film!

Can you discuss the “origin story” of the whirlpool, the Niagara Falls, as a visual motif and what meaning it held for you when you started the project?

The Falls have always puzzled me. There is something odd and goofy about the whole scene there, you know, like any tourist trap. But the Falls themselves are so overpowering and dominant. It has to do with it appearing as a primal point on the earth, an opening in the planet itself. A place where strangers lean against a rail and all experience the same thing, a Thing that is by appearances natural and big and powerful. So I could see how meeting a young woman there, someone in similar emotional circumstances, could spark a love affair that, the further it moved away from the primal point, the weaker it became, eventually erupting in a violent overthrow of the love sparked by the natural wonder.

There are tonal shifts in the story; from tenderness to abrupt bursts of violence. When working with your actors, how did you trace the emotional shifts of the characters?

We discussed how events play in our minds every day. There are jump cuts between tenderness and fear, then back again. The mind may record everything, but in recall we are very selective on how events are played. And that changes moment to moment, until the entire event itself has been rewritten hundreds of times,, though it retains it’s emotional signature. The actors and I worked out the emotional markers for each scene. Though their lines and interactions were completely improvised during shooting, we set a rhythm for how the emotions in each character would be played. So that each character was on it’s own emotional roller coaster within a scene, and toward the end the two would find harmony or dissonance because they had each hit the same emotional chord.

It’s rare to seize upon the chemistry that Agathe and Pierre share in the film on-screen. Assuming the actors did not have a history, what work was involved in creating the environment for this chemistry to develop on set?

I worked with Agathe alone in Paris for the first week of shooting. Though we had not met until then, we had been working via video chat and email for six months. So we had a level of trust built already by the time I arrived in Paris. And much of that I believe she would agree, was set when I made it clear to her that she has a say in how this character behaves. The actor is not an automaton. I told her and Pierre, as I’ve told every actor I’ve worked with since: The Actor IS the most effective special effect you could hope for on a film. So you have to treat them as an asset, a secret weapon. As to Pierre, he and Agathe only knew each other casually in their neighborhood in Paris, but they knew each other was an actor. They worked out some character details before they flew over to The States, but as far as preparing the atmosphere to allow these actors to build on their own chemistry while respecting personal boundaries — this is a task that requires a space of intimacy, which is much easier I imagine with the crew size we had, which including myself, was no more than three. I also gave them plenty of time to prepare for a scene that required more of them, like the nudity and sexual scenes, where the ‘crew’ was pared down to myself alone. This kept things comfortable and casual. We knew we were building the scenes visually, so they were the models and I was the sculptor. I think that’s an apt definition since I can see it applying to many other scenes that had no nudity at all. You have to have your actor’s ear, individually, as well as their back. When you have that in place, everyone feels comfortable putting their all into the scene, even when the actors themselves develop issues between themselves, they know they have a character to inhabit that is safe. Building that character together is key to establishing trust and intimacy.

Were there any interesting challenges you faced in the direction of the performances?

The most obvious challenge was not speaking french. Oh, I tried for sure, and I could read it somewhat. I leaned on my Spanish and worked from there with Agathe, who’s English was not yet perfected like it is today. Once Pierre was involved, things moved more smoothly since he spoke English like an American. Aside from the language challenge, there was also the unique dramatic issues that come with improvisation. You have to be prepared to shoot at all times in all places. We did a lot of guerrilla style shooting, though we had permits where we needed them like at Victoria Park at Niagara Falls in Canada. And permission from property owners. Having the camera and sound recorder ready is important because when the story is evolving, as will happen with improvisation, a place or setting may trigger a scene. A funny story that made this clear to me was when very late at night after an exhausting day of shooting at Niagara Falls, Agathe and Pierre were both wired from their performances, so they walked down to the 24 hour supermarket to do some late night shopping. When I looked outside the next morning I saw a shopping cart and one of Agathe’s boots in front of her motel room. Confronted later Pierre said they had a great time eating junk food and drinking a bottle of malt liquor and he then drove her back in the shopping cart. At that point I told him never to do anything like that again without waking me up. It’s those moments you want to be prepared for.

During some scenes, non-diegetic music is used to indicate a mood. In others, ambience heightens or establishes tone. Can you describe your approach to the sound design in the film?

On every film I have imagined, sound plays a key role. Sound is the third dimension of cinema, far superior to visual 3-D effects in conveying depth in the cinematic space because it can carry an emotional load. On this film in particular the non-diegetic sound is effectively a peek into the consciousness of Agathe, the voice in her head. I thought it particularly effective to have Claudia Carty record her songs on her own iPhone and to place a small recorder inside of her piano. This way the recording was more ethereal and, to my mind, more like the way a song plays in our minds.

The film has both icy and warm, sumptuous hues. What lead you to the visual style in the film?

I have run the camera on all of my films, with few exceptions. I trained in photography in art school as well as graphic design and painting. So the choice of color and tone is important to me because cinema is a visual medium and the elements within the photography of a scene are part of the arsenal that conveys the emotions of the scene and of the characters. I don’t shoot something because it looks ‘cool’. I shoot a scene in the tone and shadow that marks it like a post card would mark a place. In this case, we are traveling through an emotional landscape, so the scenes would change as we moved along and as day became night.

I have to say that using these techniques, what lead me there, was very much a comfort level I have with photography, especially color photography. And I remain a committed student of the use of color and contrast in cinema. Vittorio Storaro’s color approaches and Gordon Willis’ technique of embracing shadow within color, both are key figures who’s work I continue to study. So the visual style in this film can be said to be psychological landscape photography. It’s been part of the cinema-making toolkit for many years and figures in many of my favorite films, so it was a very easy fit for me.

In what areas did you face the most challenges – in the writing, casting, or directing, and why?

The most challenges I’d say was in writing and producing. The writing because you just aren’t sure if it will work, and you are battling the mind, steering things away from doubt to stay fixed and true to the vision in your head. Meaning, if you imagine a scene on an airplane, just write the scene, don’t think about the fact that you can’t afford to rent an airplane. This is harder than you think. Though screenwriter’s understand this soon enough. The challenge in producing your own work is in the elements involved outside of what ends up on the camera’s sensor. Arranging for travel for your actors, insurance where needed, and permits where required, and everything is your own responsibility. So you have to be a producer every morning and after dinner every evening, after a day’s shooting.

Not to spoil it for people, but the ending feels like it came from a different point in time. Can you explain the motives behind the selection of the final scene?

The film was originally built on the action of Agathe breaking out of a closet where her lover had locked her in, in a fit of drug induced rage. This was before Pierre joined the team and the story was reshaped. But since Agathe and I shot this scene first, in Paris, we both felt it was strong enough to include it in the final film cut. So while Agathe no longer breaks out of a closet per se, she revives herself from being tossed on the floor and when she gathers her things is confronted by a terrible scene, which originally was her boyfriend overdosed on the floor, a needle sticking out of his arm. A scene never shot. Agathe is looking at a very clean living room. But after the story’s evolution, this scene remains because of the emotion conveyed by the character Agathe. What she sees is any number of things, but it need not be something concrete, like a dead body, or her living room tagged floor to ceiling with graffiti. What she sees is an empty room. Her feeling of love sparked at Niagara Falls, is now nothing more than a memory, and a quickly fading one at that. She may feel that through it all she’s been had. No one can live at Niagara Falls and make love day and night forever. She’d hoped it would carry with her across the Atlantic. But it did not. And unfortunately she is too young to understand she can build on it. She reacts like a child. That’s the tragedy in it.

At times the film plays out like moments from a diary entry. What was the most personal element of your life that became part of the film?

I’d have to say that Pierre’s character Victor, was very much an analogue of my own experiences at that age, late twenties. I was laughing much of the time after we cut because Pierre, totally improvising in his second language, was saying things almost exactly as I had in scenes like this. The film has many autobiographical elements, except for the violence of course. The chance encounters, road trips, sleeping on floors, and drinking too much, loving too intensely—these are from direct experience. You can’t fake these real events—you have to know them to write them.

Are you working on anything new?

Currently I am finishing up my documentary of the American visionary artist Paul Laffoley, The Secret Universe Of Paul Laffoley. I will begin assembling a documentary on the sound artist Tod Dockstader after that. As for narrative, I have two films in development. One will be shooting this spring titled The Frozen Sea, which plays a bit like Hitchcock’s Spellbound mixed with The Lathe Of Heaven. The other in development is a experimental film noir which I am working on with the dutch actor Dieter Jansen, who lives and works in Los Angeles. That film is titled New Netherland and we plan to shoot that in 2018.